4. Before you start…

As we saw in the last section, careful planning is the key to successful research. Even before you start the planning process, there are two ways to make your research valued and competent.

Part A of this section provides an understanding of some key research theory and concepts will help you. In this section we aim to explain these as simply as we can, and to use as little jargon as possible. We will define essential technical terms throughout this toolkit and there is an additional glossary that will help you to understand and learn some of the language used in research.

Part B examines some broader considerations – the ethics of research and how it is carried out, especially in a community setting. This means thinking about issues such as participation, confidentiality and equal opportunities.

A. Research theory

Understanding basic research theory will:

- Enable you to design your research.

- Give you a better understanding and make you more aware of your own perspectives and values which you will inevitably bring to your research.

- Give you a better understanding and ability to critique any research reports you need to read for your research i.e. what is already known about your subject.

Here we cover the principles that underpin research by defining and explaining some common research terms:

- Quantitative and qualitative research.

- Strategic approaches.

- Reliability and validity.

- Triangulation.

Though these terms may seem daunting, we lead you step by step through the definitions and provide you with examples.

There are several different approaches to doing social research. Choosing an appropriate method for your research is not just a practical issue, it is also a question of how we make sense of our situation or the world around us and the most appropriate way in which to study it.

At this point we need to introduce the two overarching approaches, quantitative and qualitative research.

Quantitative and qualitative research

Research is generally referred to as quantitative or qualitative, indicating different kinds of information which are collected.

Quantitative research collects data that can be added up and used to generalise to the wider population being studied. It is concerned with collecting numbers and measuring things numerically. It is mostly associated with:

- Large-scale studies.

- Evidence about the relationship between local issues and their wider context. For example ‘50% of children on this estate experience poor health as opposed to a national figure of 30%.’

- Being able to identify a problem or the existence of an issue.

- Providing the context – the extent to which something is happening.

Qualitative research seeks to gather data that is non-numeric. It provides depth and is associated with:

- Small-scale studies.

- Understanding or explaining issues – why or how something has happened.

- Description and richness in detail.

- Information about attitudes, views and feelings.

- Looking at things in context, stressing relationships and interdependencies.

- Understanding why something has or hasn’t worked.

For many years, there was debate about which kind of research, quantitative or qualitative, produced ‘truth’. Now it is recognised that both kinds of information are useful. Many researchers use a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to identify the extent to which something is happening and to understand why this might be the case. This is called a mixed methods approach. The methods you use depend on what you want to find out, as well as the budget for your research project, and how much time you have.

If you want to promote volunteering in your area or to lobby for more support for volunteers, then it would make a good case of you can tell people about how many people are volunteering and what proportion of people are volunteering and also include some case studies of people’s experiences.

Strategic approaches

First we need to consider the overall research strategy that will be used and the different methods that will fit into it. Various research methods, such as interviews or questionnaires, can be used for each of them. Some methods are more appropriate to certain circumstances than others, but there are no specific rules saying which method is best suited to each approach. What is crucial is making sure that you are using the methods that best help you find out what you need to know, within the limits of your time and budget. Three strategic approaches particularly relevant for community groups are:

- Surveys

- Case studies

- Action research

Surveys

‘To survey’ can mean ‘to view comprehensively and in detail.’ Implicit in the notion of a survey is that it is broad in its scope. Surveys generally relate to the present state of affairs and may be updated, like the UK national census, which is conducted every 10 years. The census is an example of a survey that aims to cover 100% of the population. Most surveys are less ambitious than this, using sampling techniques to identify a smaller group for study and then generalising their results to the broader group. See section 5 for guidance on sampling.

A common problem for many researchers is that they only get a small response to their survey. This can be because they have not established good enough links with the population they are trying to survey, or that people don’t think that the issue is relevant to them. It can also be because the wrong approach has been selected – the research might be something better explored using one of the approaches described below. This is something that you need to consider in the early stages of your planning as part of your research strategy

Note that a survey is not a method but a research strategy, which can make use of a variety of methods such as interviews, questionnaires and observation.

Case studies

The term ‘case study’ is used in many different contexts, but here we use case studies to mean a strategy for research, focusing on one particular or specific case in context. They lend themselves to exploring situations that can be typical, extreme, available, interesting or unique.

Case studies are a spotlight on one instance, one person, one area or one organisation.

The case study is the opposite of a survey; it is not a mass study and does not seek breadth, but depth. The idea is to use more than one method to collect data relating to the case study.

Your organisation may choose to focus upon a particular neighbourhood as a case study. For example it may be unique in having a community-led initiative that has reduced crime to extremely low levels. Or you may want to study a youth group that has developed interesting ways of working with young people around parenting.

When choosing case studies, you should consider what you are trying to get across to people. Often people use an extreme example of the progress someone has made as a result of engaging with a particular activity. This can make a good story but if it only ever happened to one person, is there a point to telling it? It might be more useful to use an example of someone whose experience is fairly typical of the stories that people in your organisation tell.

You may take a small community organisation as a case study because it is typical of small organisations and explore location, development and changes, social context and organisational type in order to draw out what makes it work and key issues.

Action research

The purpose of action research is to improve practice. It is well suited to conducting research in the workplace or on a specific project, as it feeds findings in to the ongoing project. It is also a strategy that places practitioners – people from inside the organisation – at the centre of the research process

The researcher or practitioner, usually in consultation with the group they are working with:

- Identifies a problem.

- Thinks of practical solutions to solve that problem.

- Implements these solutions.

- Collects data on any changes that take place as a result of this implementation.

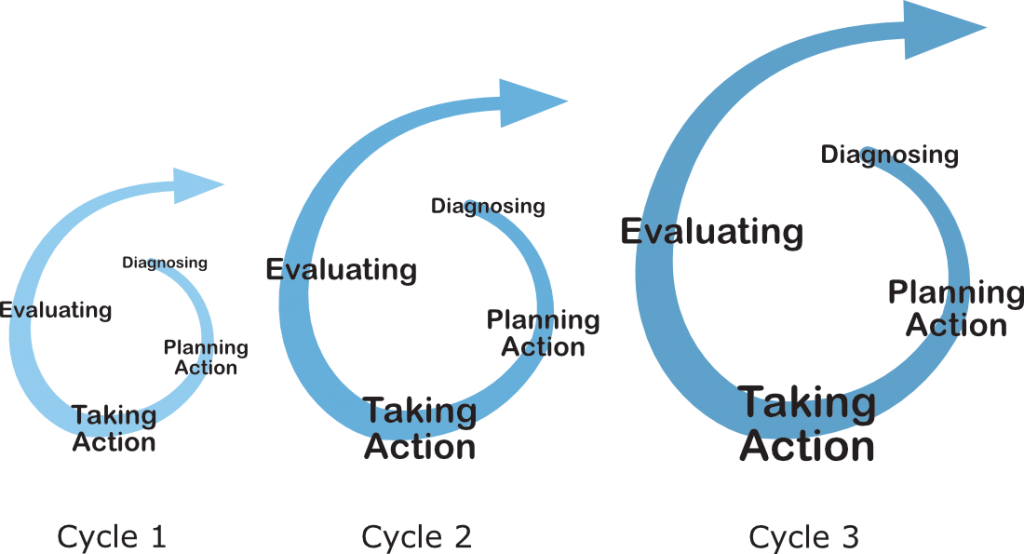

In some cases the findings will lead to a new investigation that requires the action research cycle to be repeated – as illustrated in figure 2 below. More issues are then identified, and more solutions are thought up or confirmed. This process of research is an ongoing one, using a systematic approach for the definition, solution and evaluation of problems, issues and concerns. It helps generate local solutions to local problems.

Fig. 2 – Doing Action Research in Your Own Organisation, Coughlan, D. and Brannick, T. Sage 2001 (3rd Edition 2009)

Action research is a form of participatory research and other methods are discussed elsewhere in this toolkit. In section 3 we also discuss the spectrum of participation that places the different roles that communities can have in the research process on a spectrum of how much say local people have in how the research is conducted.

Reliability and validity

In a research context, the terms ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’ have specific meanings. Understanding these can help you with your research design.

Reliability means that the data collection methods you use do not have an undue influence on the results you obtain. Your findings would be similar to someone else’s if they were to repeat your research. For example, if someone was asked to complete the same questionnaire twice, they should generally give the same answers. If they don’t it may mean that the questions are ambiguous and open to different interpretations. Piloting – trying out your research with a small group of people as a practice run – is crucial to ensure that the method you have chosen works for your research and that the information you collect is reliable.

Where there are several researchers gathering information it is important that they have a shared understanding of how they will collect data.

Validity refers to the notion that the information you gather actually is about the topic in question. This might seem a fairly simple thing to deal with but is actually a complex process. For example, in an interview, the respondent may give the replies that they think the interviewer wants to hear, or they may not want to say things that are critical of others, or they may just go off the point. If this happens, we could say that the data collected is not valid; it is not relevant to the topic (though it may be worth exploring at a later stage).

Research will also be seen as invalid if the people who take part in it are not representative. We explain how to make sure you have a representative cross-section under ‘who to talk to‘ in section 5.

Triangulation

There is no one ‘right’ method of research that will work for any given circumstance. Various factors influence which methods give you useful information, and there are no guarantees that just because one method worked well once it will do so again. Triangulation is when you don’t rely on one method but you use a combination of two or more approaches. It is a building surveyors’ term which means checking out your measurements or findings from three different angles or perspectives. We can apply it to community research by making sure we use several methods of obtaining the information we are looking for.

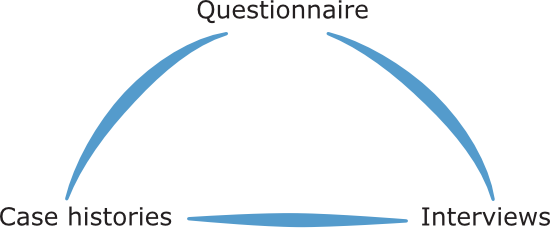

One way of dealing with this is to use several different data collection methods as a way of comparing the information for consistency and irregularities. See figure 3 below. You could also evaluate how far your research findings compare to other similar research that has been carried out; does it reach very different conclusions or not? This is called external validity. This is not a fool proof measure as other people’s research may not be internally valid and your research may cast new light on a situation. It is only one way of evaluating validity.

You might find, for example, that a postal survey on your housing estate highlights repairs as an area of concern. You might want to add to this some case histories of the problems people have had with getting repairs done and interviews with housing officers.

Fig. 3

You can also triangulate your findings with other research data. Has anyone else done any similar research, maybe in another community, and found similar things? Or is there a piece of academic or government research that has evidence that supports your research. Here is a tool that might help you find useful data

Government statistics can be found on the ONS website . This site also provides links to local data sources.

Part B Ethics of community research

“Ethics – people tie themselves in knots over it.” (Researcher)

Researching the community means that you will need to take account of what people actually say even if you do not always agree with it. It is also important to make the methods and results of your research accessible to others so that you are accountable for the information collected.

People should only participate in research with their full consent. This means that they fully understand what you are trying to find out and why, who has asked for the research to be done and who is funding it, how you will use the information they provide and who will see it. They also need to know that they can opt out or remove their permission for you to use their information at any point. It is often useful to get people to sign a form to say that they have given their consent. If you are quoting them directly or using a case study to tell their story, even if you are not revealing their identity, it is a good idea to ask them to review what you write about them before you produce your final version. People can also be partners in the research process where there is a two-way flow of information between the researcher and the person being researched.

Like much social research, community research often involves asking people about their lives, their feelings and their experiences. Some research methods will ask more of people than others, for example, a long one-to-one interview will reveal more about someone’s life than a quick questionnaire.

You should think carefully about whether people are likely to find any of your questions upsetting. You might not be asking people directly about their mental health, abusive relationships or bereavements but these issues could mean that people are vulnerable and you could risk digging up difficult issues for them. You should probably not be asking about such issues directly unless you have received specialist training in the subject or you can assist them to receive support – but even then you should ask yourselves ‘ethically – should we be doing this?’

How you decide to conduct your research will raise ethical issues such as equal opportunities. We can consider equal opportunities in different ways. We can make sure that any data collection methods we use are equally appropriate to everyone involved in the research so that everyone is potentially equally able to contribute. We can target those people who are generally excluded from research and provide extra support so they are able to put their views forward or be involved in the actual research process. We can also make issues of inequality the subject of our research.

See the betterevaluation.org Community Researcher Manual

There are a number of approaches to ensure good practice in your research design.

Strategies for being inclusive

- Recognise that people are different – in any community or group of people there will be differences such as ethnicity, sexuality, family structure etc.

- Use appropriate data collection methods suitable for people with different needs, for example discussion groups or phone interviews rather than written questionnaires for people who are visually impaired.

- You can use technology to enable people to participate in your research but you should also make sure that you are not excluding people who, for example, don’t have access to a computer or who are unable to use the technology.

- Provide support to take part on equal terms, such as interpreters paying expenses for travel or childcare.

- Use different formats such as audio, Braille, different languages or large print, both in the research process and for presenting findings.

- Ensure meetings are held at suitable times and venues for all.

Strategies for recognising differences

- An awareness of the different needs and experiences of different communities will add to the richness of your research.

- Accept that there may be majority and minority views.

Participation and consent

Are people aware that they are part of a research project? Have they given their consent to be included in the research? This is especially relevant when using methods such as observation or if you are making use of existing research. Have people taking part given their informed consent for the use of their information?

Confidentiality

Have people disclosed sensitive information about themselves that could be traced back and attributed to them? Even if you don’t name them, you could say something about them that others would recognise. If you are researching in a particular community, then it is quite likely that people might be able to recognise individuals that they know if you say too much about their circumstances. You don’t always have to give someone’s name to enable people to work out who has made a comment or whose case study this is.

At the start of your research ask yourself:

- How much information and feedback should I give back to the people I have been working with?

- Who now owns the information?

- Are people aware that research is being carried out?

Data protection

You also need to check you are complying with the General Data Protection Regulation 2018 (GDPR), which supersedes earlier legislation. It is the law which governs those who hold and deal with personal data – anything from which a living individual can be identified, either because you have included their name or through simple deduction. It applies to manual systems (e.g. card indexes and filing systems) as well as information held on a computer database. It does not intend to stop you collecting personal data, but sets out how personal data should be obtained, stored, used and disposed of. It applies to all organisations including small community groups.

For the purpose of research the most relevant are the sections covering obtaining consent and how data is used. You should make people aware that you wish to record information about them and what you will and won’t do with the information. Stricter conditions apply to the processing of sensitive data, which includes information relating to racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or other beliefs, trade union membership, health, sex life, and criminal proceedings and convictions.

People should be asked to give explicit consent if this information is being collected. People have a right to access any information about them held by an organisation. Organisations should ensure that the information they collect is relevant to the purpose for which it is collected and only held for as long as it is needed.

You should also ensure that all recorded data is kept secure and private, hard copies should be kept in locked cabinets, Information held on computers should be password-protected with robust passwords. It is good practice to detach respondents’ names and addresses from the rest of the information about them after checking the data. Either store them separately or destroy the records that show people’s identity.

Top 5 tips for charities from Information Commissioners Office.

Detailed information and guidance

The regulator for the GDPR is the Information Commissioner. This is where you can find more information about data protection and also where to make complaints if you think your data has been wrongly used.

The Information Commissioner’s Office

Information Commissioner’s Office

Wycliffe House

Water Lane

Wilmslow

Cheshire

SK9 5AF

Tel: 0303 123 1113 (local rate) or 01625 545 745 if you prefer to use a national rate number

To email the office you should go to the website below and send an email using the link provided

There are regional offices in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland