6. Research methods

This section looks at the actual methods you use to carry out research. We saw in the introduction to research theory in Section 4, that community groups often use three approaches: surveys, case studies and action research. Whichever approach you use, you will need a combination of research methods to carry it out. These are the tools for doing research and you can use them in different combinations according to your research purpose.

The methods community groups are most likely to use are covered in the next 4 parts

Part D Other methods, including participative methods, user panels, written consultations, observation, oral history and story-telling, participatory and creative approaches.

A. Questionnaires

Questionnaires are one way of collecting information by asking a selected set of people a set of questions. Usually they are structured, asking the same questions in the same order. The ten yearly UK Census form is an example of a highly structured questionnaire. Questionnaires are a widely used research tool. They can be administered over the telephone, face-to-face by an interviewer, or self- completed as a written exercise with little or no direct contact between the researcher and the respondent – they can be distributed by hand at an event, sent by post or posted on a website or social media platform for people to complete on line.

They are useful for

- Gathering data from large numbers of people.

- Gathering straightforward information about something specific.

- Providing statistical data.

They are less useful for

- Collecting detailed information and explanations.

- Finding out why someone holds a particular view or opinion.

- Engaging people in answering the questions.

- When you have few resources to pay for printing, postage etc.

- When some people may not be able to use or have access to a computer.

- When issues of literacy, language and disability means not everyone is able to read or understand the questions.

In this part we look at which questions to ask, types of question, questionnaire design, appearance and piloting.

Online surveys

You may want to think about using an online questionnaire, if you think that your respondents would be likely to have the resources to complete a questionnaire online. This can be a much cheaper and easier way of distributing and collecting questionnaires. There are a range of online tools suitable for community groups.

Deciding which questions to ask

The questions you need to ask should stem from the initial questions you identified at the beginning of the research, or from any subsequent reassessment once you have collected some background information.

Start by listing all the information you are trying to find out. Then identify some questions you need to ask in order to find that information. You could do this by laying the list out on cards in as logical an order as possible and drawing out specific questions that relate to each piece of information. You will probably need to edit down this initial list of questions making sure that each question you decide to keep relates back to your initial research questions. Once you have been through this process you will be in a position to design your questionnaire. It is a good idea to review whether each question is really something you need to ask to provide the information you need or whether you just think it would be good to know the answer. Remember – the fewer questions you have, the less time it will take people to complete and the easier it is to encourage people to do it.

Think about how you will analyse the answers when you design your questions. See section 7 on how to analyse your findings.

Types of question

Each question on your questionnaire will be either an open question or a closed question.

Open questions

These require an answer from the respondent that has not been pre- determined by the researcher. The question allows for an open-ended reply.

Open questions can help people to give you more detailed answers but can make it more difficult to draw out key themes and generalise responses – for example, different people might describe the same experience in different ways and you might struggle to tell from their answers that they are making a common point. Open questions also need lots more time to analyse when you are looking at your responses – this is dealt with in section 7

Closed questions

There are a limited number of possible responses to these questions where the researcher has asked a yes/no question or has provided a list of possible answers.

Yes

No

Never

Less than 3 times a week

3 times a week or more

Closed questions are simpler and quicker to analyse but you are also putting a limit on what people can tell you – their answers to your closed questions might only give you part of the picture and won’t help you to understand why something happened or why people think this.

Open and closed questions can both be asked in different ways, outlined below. Make sure your questions include an instruction to the respondent to ‘tick all that apply’ or ‘select up to 3 answers’

Lists

A list is made and the interviewee selects all those that are relevant to them.

tick all that apply

Pantomome

Coffee morning

Disco

Aerobics

Harvest Festival

Barbecues

Concert

If you use list questions it is a good idea to end with an ‘other’ category. Include a space for respondents to tell you what their answer is.

Category

This gives a set of categories and the interviewee can only fit into one of the answers. It is often used for age categories.

11-17

18-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-59

Over 60

Grid

This is a list of choices which can also be represented as a table or grid that helps to answer two or more questions at the same time.

| Aerobics: | |

Older people’s club: | |

Youth club: | |

Coffee morning: | |

IT training: | |

Ranking

The interviewee is asked to place something in order of rank or importance.

Please place the following in order of importance with 1 being the most important and 5 the least important

| New bus shelters: | |

New play area for children: | |

Security fencing around community centre: | |

CCTV for shops: | |

Kick about for sports: |

Only one number should be selected as an answer

1 = I make all the decisions

2 = I help to make the decisions with others

3 = I help sometimes to make the decisions

4 = I have never helped to make any decision

5 = I am not allowed to make any decision on this matter

| What time the centre opens and closes: | |

Who is allowed in the building: | |

What activities are going on in the building: | |

Where activities should be advertised: | |

What the priorities are for funding: |

Quantity

The answer is a number, without any other information.

How many adults use the centre on a daily basis?

How many children use the centre on a daily basis?

How many of your users have a disability?

You will notice that in each of these examples, clear instructions are given so that the respondent knows exactly how you want them to answer the question.

If you use lots of open questions you will probably need to read them all individually and categorise the responses as described below for analysing interview records. This can take a long time if you have a lot of questionnaires (over about 50). If you want to ask a lot of open questions then you might consider using another research method, such as interviewing people.

Questionnaire design

Wording

It is important to ensure that you use sentences that mean the same to everyone. Different words mean different things to people, so some sentences may be understood differently by the respondent.

A great deal

Sometimes

A certain amount

Very little

How would you interpret this? What do a great deal and a certain amount mean?

This example is clearer.

Every day

Once a week

Once a month

Never

You want people to answer all the questions so that your statistics, percentages, numbers and other analyses are valid. It is important that people understand the question otherwise they may miss out some parts of the questionnaire.

Is this question straightforward?

Bowes Primary

Nightingale Primary

Huxley Primary

St James Primary

This question assumes that the person filling in the form only has one child and the child goes to one of the named schools. If the respondent has more than one child what do they do? Do they tick all that are relevant? Put the ages in the box? Try to squeeze in the answer under the section? The respondent may simply leave it blank.

You should, in many cases include a category ‘other – please state’ and give people space to write in their own answer. You might not have thought of all the possible answers. In the age category question above, there might not be any other possible answers, but in the question about where your children go to school, it is possible that the children are educated elsewhere, or are home schooled so you need to give people the chance to tell you that.

You should also give people the chance to answer ‘don’t know’ or ‘this is not applicable to me’ This gives you more information than if someone has not answered the question at all.

Points to remember

Memory

When answering a question such as ‘what subjects did you take at school?’ some adults will be able to remember what they did, others will not remember at all. If they forget to include one of the basic subjects such as English or maths, do you assume that they didn’t study it, even if you know in reality they probably did? It might be better to make a list people can tick, to ensure answers are more accurate.

Double questions

Be careful not to ask two questions in one, such as ‘Do you go to arts and English evening classes?’ If they answer yes, does this mean they attend both classes or do they only go to one? You should ask two separate the questions. This is not the same as the grid question above, when you are enabling people to answer the different elements clearly.

Leading questions

The way a question is structured can force an interviewee to answer in one way only. Remember that though you may be carrying out your research to prove something, you discredit your research if you ask questions such as the following:

The answer is likely to be yes, as this is the answer you appear to want. You could ask the question in the following way

Yes

No

Don’t know

Presuming questions

You could phrase this question in the following way

Better than before the merger

The same as before the merger

Worse than before the merger

Don’t know

Useless questions

Beware of asking questions that provoke a useless response.

This could get a silly response such as ‘fly to the moon’ or ‘I never will win that much money, so what is the point in thinking about it?’ In general, questions that start ‘what would you do if….’ should be avoided as respondents will only be guessing about what they might do.

Sensitive or offensive questions

An obvious example could be ‘How old are you?’ Instead it might be better to put ages into sections and ask the interviewee to tick which one they fit into. See the example for categorising questions above. Other areas that might be sensitive include how much money people earn or the benefits they receive, and questions about health conditions or sexuality. It might help to have an option of ‘prefer not to say’. You could also put these questions at the end so that if people are put off by these questions you have got the majority of your questions answered. Use your common sense – or ask someone you know if they would find it offensive or embarrassing. Think hard about whether you really need this information or not.

Gender and sexuality are becoming more complex and you might need to reflect this in your questions with options such as ‘none of the above’ as well as ‘prefer not to say’. These are highly sensitive issues and you should only ask about them if you really need to.

How to organise your questionnaire

A front page or cover – on the cover, including

- The name of your organisation.

- Names of any sponsors.

- The purpose of the research – why you are doing it and what the information will be used for.

- A return address and date.

- Confidentiality and what this means.

- Prize draw to encourage responses – if you have names and contact details.

- How long it will take to complete.

At the end of the questionnaire you should thank people for filling it in.

If you use an online questionnaire, there will be spaces to include this information.

You should number all the questions and make sure that the question and the answer are on the same page and not broken by a page break.

Make sure the size of the text is legible, especially if you are targeting older people or those who might have sight impairments. If you are designing and on-line questionnaire, make sure you follow guidance for people with limited vision or learning difficulties, such as dyslexia, which can be affected by, for example, the colours you use. You can find advice on the subject here .

Skipping questions

If your questionnaire will be completed by a wide range of people it is likely that not all of the questions will be relevant to everyone, especially if there are lots of questions. For example, if you want to ask local residents which schools their children go to, you could include an initial question that asks:

If the answer is ‘none’ then you can say ‘if none, turn to question number x’. The respondent can then move on to the next question that is relevant to them. You need to be well organised if you do this, making sure that the logic of your questionnaire works (see piloting, below) and that this logic is mirrored when you do your analysis (see section 7). If you use an online survey programme then this is easy to set up and the respondent is taken straight to the next relevant question. However, some tools don’t allow you to do this in the free version of their software, only in the versions you have to pay for.

Instructions

You will need to provide instructions to people filling out the questionnaire.

- Never assume questions are obvious and straightforward.

- Give specific instructions for each question e.g. circle/tick or delete, tick one only/tick up to 3 or tick all those that apply.

- Give clear instructions when people can skip questions.

- Provide examples of completed questions.

Serial numbers

You can use serial numbers even if you have only a few questionnaires to go out, especially if they are being distributed from different places, so you can identify the place and date of distribution.

Put the serial number on the front cover e.g.

- 0087 – the 87th questionnaire

- 003 – location/street/group

- 0119 – Jan 2019

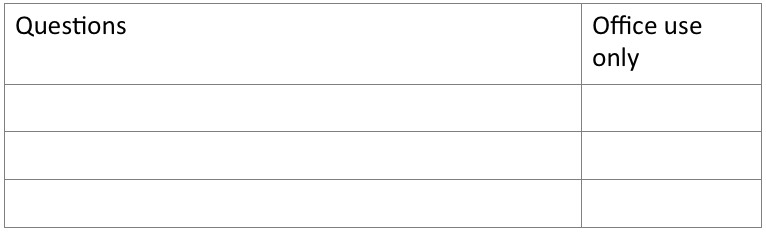

Coding boxes

You may need to include these, depending on how you are going to analyse the responses. This will help to sort out the raw data once the questionnaire has been completed. If you are coding responses manually, and you have a lot of questionnaires, you will need coding boxes on the right hand side of the sheet in a column headed ‘for office use only’

Layout

- Make sure that you put adequate spaces between the questions, as this will help people to distinguish between them and make it easier to analyse later.

- Make sure that you keep the questions in some order. Start with straightforward questions then move onto ones that need a more thoughtful response. Keep the questions in categories: don’t hop about with questions on different topics. This way people will know where they are – you do not want to confuse them or put them off filling in your questionnaire. You can label the categories, especially if it is a long questionnaire, for example ‘about you’, ‘what you have done in the past,’ ‘what you would like to happen in future’.

- Keep the response boxes in order. Try to keep them to the right of the page and in line as you go down the page. This is not only more pleasing to the eye but easier to manage when analysing information.

- Using the same types of questions with similar layout can increase boredom but make it easy to answer. Using a range of different question formats reduces boredom, but can be more confusing to answer. This kind of issue can be resolved at the piloting stage.

Piloting

When you have completed the questionnaire, put it down and go back to it later for a second look. Then give it to some people who haven’t been involved in the planning to try it out. Ask them if there were any problems. Could they follow the instructions? Did they understand the questions? Were the options given appropriate? You should also try coding their responses. Did they answer all the questions as you had intended? Did they follow instructions, for instance, circling or ticking as you had asked? Did they make extensive use of ‘don’t know’ or ‘other’ options? If so, you may need to rethink some of your categories. You may need to go through this stage more than once. If you use online survey software there should be a facility for you to send it to a few people to test the questions and the functionality of the questionnaire.

This may seem like a lot of trouble but it will make your questionnaire better and make sure you find out the information you are looking for when you distribute it widely.

B. Interviews

One to one interviews help you to obtain more complex information – when you want to know ‘why?’ as well as ‘what?’ or ‘how many?’ The distinctive features of one-to-one interviews are that people give their informed consent to take part and they are pre-arranged. The researcher sets the agenda and explains context of the interview.

They are useful for:

- Getting the views of people who feel uncomfortable in a group.

- A verbal approach for people who find written questionnaires difficult.

- Allowing flexibility, so that new issues and ideas can emerge.

- Generating detailed explanations and feedback and exploring sensitive and personal issues.

- Getting high response rates.

- When it would be impractical to get a group together.

- Creating a positive and empowering experience.

- Getting detailed specific views.

- Getting people’s opinions.

- Situations when someone might need encouragement/support to answer questions.

- Understanding complex issues.

- Getting in depth responses from a smaller number of people.

- Following up themes that emerged in a questionnaire.

They are less useful for:

- When interviewers need training – this is advisable.

- Generalising your findings – you are likely to be asking a small group of people.

- Providing much statistical information.

- When you haven’t got a lot of time or resources.

Interviews can also:

- Be intrusive for people.

- Provide few standard responses, making it harder to analyse.

- Be unreliable due to possible interviewer effect (see below).

- Require high costs and resources per individual interviewed.

Types of interviews

When using interviews as a way of collecting data, you will have to decide what type of interview best suits the research question.

Fig 7

Fig 7

Interviews can be completely unstructured or highly structured. Consider the information that you need to collect before deciding on the format.

Structured interviews are carried out face-to-face using a questionnaire with a standardised format and a predetermined list of questions with limited option responses. Standardisation in terms of wording, range and order of questions means that analysis is relatively easy. They are often used to collect large volumes of data from a wide range of respondents and lend themselves to the collection of quantitative data.

Unstructured interviews are as unobtrusive as possible, with certain themes for the respondent to pursue in their own way. They are most useful as a method of discovery rather than checking out answers to specific questions and lend themselves to in-depth investigation of people’s experiences and feelings.

Semi-structured interviews are more open and flexible, although still with a clear list of issues to be addressed and questions to be answered. Their flexibility allows respondents to develop ideas and expand on issues if they choose. You could start this by asking some structured questions but then asking people to tell you more about their answers.

Interviewer effect

In a one-to-one interview the focus is on the relationship between the two people. If something gets in the way or adversely influences this relationship it can affect the quality of the information generated. Age, gender, ethnicity, appearance, social status and speech patterns all affect how people respond to someone and will influence the trust and rapport between the researcher and the interviewee. The skill of the interviewer lies in striking a balance between maintaining neutrality (in views and appearance) and establishing rapport.

Questions need to be worded carefully to avoid leading questions, as in questionnaires.

If you have chosen to use interviews as a way of engaging with people and encouraging them to talk in depth about their personal experiences, you should still try to remain neutral, while establishing an empathetic relationship with the interviewee. If the aims of the research are specifically to help people express and reflect upon their experiences and make connections you will need excellent communication and people skills. The ability to listen actively, to summarise and reflect back what your interviewee has said and to pick out and develop key points are all needed. If you have chosen this approach be aware some people will expect interviewers and researchers to be ‘expert’ and to appear objective and neutral.

All of this is particularly important if the interviewer is known to the interviewee. Sometimes it is easier for interviewees to talk to someone they don’t know if they are discussing sensitive or confidential issues. Equally, interviewers can find it easier to be neutral if they don’t know the interviewee. However, sometimes people will be able to be more open with someone who has the same experiences as theirs. (See section 3 on insider and outsider researchers)

Who to interview?

As interviews can take quite a long time and generate a lot of information, they are usually done on a much smaller scale than self-completed questionnaires. In qualitative research, respondents are usually chosen on the basis of non-probability sampling. This means that they are handpicked or volunteer to participate in this stage of the research. They are not expected to be representative of the population at large. They may have a special contribution to make to the research or a particular insight to give, based on their experience or position within an organisation.

If you do want to use interview data to make comparisons and generalisations then your way of choosing respondents might need to be more representative and follow guidelines and methods of probability sampling.

Approval

Will you need permission to interview someone because they are under-age or vulnerable? You might need a parent, relative or other responsible adult in the room with you. You might need to be approved by the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS). You should explore these issues before you start your research. You should also think about having identification cards saying who you are, where you are from and a short written summary about what the research is for, which you can give to the interviewee.

If you want to do an audio or visual recording of the interview you should obtain permission in advance from those you are interviewing. Some people are reluctant to be recorded in this way and you should respect this. For example if you are talking about sensitive issues, people can feel more anonymous if there is only a written record. If the interview is with a child or vulnerable adult you should obtain written permission from an authorised source.

Where and when to hold the interview

The time and the location need to be selected on grounds of access for the interviewee and the personal safety of both parties. You should arrange the interview at a time and location that suits the interviewee. You should have a space where you can speak privately and not be overheard or interrupted. If you are going to interview someone in their home you should be aware of personal safety issues for the interviewer. You should again consider whether the space is private and uninterrupted. Again, you should decide how you are going to record the interview and, if you are planning to use a recording device, ask for permission to record the person before you start.

If you are going to conduct a telephone interview you should book a time to speak to someone and find out what number to call them on where they are least likely to be interrupted. You should tell people how long the interview is likely to take and how you are going to record the interview. If you are doing lots of interviews or you are taking notes it is best to use headphones. Make sure you are working somewhere you will not be overheard or interrupted.

Interview structure

Make sure the interviewee understands the purpose and context of the research that you are involved in, the format of the interview and how long it will take. As stated above you may want to take a written sheet containing this information. Set up any recording equipment in negotiation with the interviewee.

You should also make it clear how you will be using anything they say. Will you quote them anonymously or will you want to attribute their comments to them as a person or a representative of a specific organisation? If so you should arrange to show them any quotes you are planning to use in your write up so that they can approve them.

Ask easy questions to start, together with questions about their background or interest in the topic area. Use trigger questions or materials to get them to talk in more depth. Towards the end ask them if they have left anything important out or if there is anything they want to add. Always thank them for their time and you can ask if they would like to read through your notes or analysis to make comments.

Recording data

There are only a few choices about how to record interview data: written notes, audio- taped interviews and video-taped interviews.

Relying on one method alone can be risky. For example, if the equipment fails then your interview is lost. This is important when conducting interviews out of the office. Keep things as simple as possible. If you do use equipment, make sure that you have fully charged your device, have back up batteries or can access a mains point in the interview location.

Some researchers use both notes and audio taped interviews. Notes need to be done during or immediately after the interview but there is no need for electrical equipment and you can record non-verbal language or cues and context.

It can be helpful to have a second researcher primarily taking notes while the other manages the interview.

Audio taped interviews are useful as a permanent record of what was actually said but the presence of the tape recorder/phone can inhibit people. Transcribing can take three times as long as the interview itself, although summaries can be made instead of a full transcript.

Costs

The main element is time to set up and run the interviews and to analyse the information. There may be some expenditure on travel, tapes and photocopying. You may need to hire an appropriate venue to conduct the interviews. It is more expensive to use two researchers but the quality of the reporting may be better. You could commission a professional transcriber to do this job. You would need to find out what it is likely to cost in your area – ask employment agencies or at a university where they are likely to know of people who transcribe research interviews.

C. Focus groups

A focus group is a group interview or discussion with about six to twelve people meeting together to share opinions and experiences around a specific topic or issue that has been decided in advance. They need to be led by an experienced facilitator.

They are useful for:

- Exploring attitudes and experiences about less sensitive or less controversial topics.

- Gathering in-depth information as the discussion gets people talking and provides triggers to people’s experiences.

- Getting people to relate their own experiences.

- For getting a range of opinions and suggestions for future development of your service or activities.

They can be used in conjunction with other research methods. For example as the first stage of a research process to discover what issues and concerns are important and you can then design your questionnaire based on what people told you were important issues.

They are less useful for:

- Asking lots of questions – you can do more in in a one-to-one interview, because of the time needed for group discussion.

- Dealing with confidential or sensitive issues.

- Generalising your findings – even though a range of opinions is generated – as they are the opinions of your focus group members only.

- Getting an appropriate balance of people together at a convenient time and place can be difficult.

Points to be aware of:

- The need for an experienced facilitator and for an observer.

- The difficulty in recording what people say.

- Occasionally people will agree with points made in order to avoid confrontation and argument.

- A few people may dominate the discussion – though an experienced facilitator should prevent this.

- Sometimes people can re-inforce negativity and it can be difficult to identify what could be done to make things better.

- The group may not challenge each other and therefore reach a conservative agreement.

People should be paid their travel and childcare costs. Sometimes they are also paid a small amount of money (£10) or given a gift such as vouchers, in recognition of their time.

Designing your questions

Your starting point will be the research questions you have already identified.

Place these issues in logical order and develop questions. Start off with a general and fairly straightforward question to get people talking. Use each subsequent question to narrow the discussion and focus on the issues, moving from the general to the specific. For example move from what has happened to how it felt and then to suggestions for improvements if your research focuses on services. Your questions should not change topic randomly as this will inhibit discussion from flowing. Each question should relate to a specific issue but be broad enough to encourage a group response. This will include the sharing of experiences, ideas and opinions. Avoid closed questions that result in yes or no answers.

When designing questions for the discussion you should also list prompt questions after each question explaining what you mean and encouraging the initiation of discussion or further elaboration. Discussion should last no longer than 90 minutes – obviously this limits the number of questions and issues that can be discussed.

If you know people are going to want to complain about an issue and use your focus group to let off steam, it can be best to get that question out of the way first before you move to other issues but the facilitator must ensure that the discussion moves on and that all of your questions are covered.

Who should be in the focus group?

Members of focus groups need to have had direct experience of the topic or issue for discussion, or share particular relevant characteristics, for example:

- All have used local public transport.

- All have experienced being given the same diagnosis.

- All live in a particular locality or area.

In this way all the members of the focus group will have something in common. They are also likely to have differences between them such as gender, socio-economic status, age, sexuality and disability. You will need to decide how much the group needs to have in common and in what ways they are likely to be different from each other in order to provide a rich and detailed discussion with a range of views and opinions.

The groups can be focused on people with things in common – people of the same ethnic group, gender, sexuality or age, or people who are in long term unemployment or who live a particular housing estate. This can enable comparison between groups (although you will not be able to generalise your findings) or may highlight needs for different groups. Ideally when recruiting use informal networks such as places of worship, community organisations and schools. Ensure you explain to people what you are researching and why.

How many should be run?

Often you will need to run more than one focus group. Some researchers may meet with the same group several times to explore one issue in depth. It is unlikely that a small organisation will have the resources to do this. In other pieces of research you may need to cover the views of people living in different areas, or with differing needs.

Where to hold a focus group – As with holding interviews, the venue should be:

- Local to where people live or work.

- At a time that people can attend.

- Accessible to people with different needs.

- Warm and comfortable with refreshments provided.

- An informal environment where people will feel free to express themselves.

- A space where you will not be disturbed or interrupted.

Running the focus group

Before the group starts check that any equipment is working and make sure the seating arrangements will enable all group members’ voices to be heard – this will normally be sitting in a circle or round a table. Ask people to complete a short demographic questionnaire and explain that it is important to know the focus group’s make-up.

Practical issues:

- Welcome people and put them at ease.

- Say when the session will end and go over housekeeping arrangements such as toilets and fire exits.

- Offer refreshments and give out name labels.

- Introduce your organisation, what you do and why you are running these focus groups. Explain how a focus group works and how it will contribute to your work or research.

- Ask permission to record the session and explain the role of an observer and facilitator.

- Establish ground rules for the meeting.

- Emphasise the confidential nature of the focus group and what this means in practice i.e. opinions and experiences, if quoted, will not be traceable to specific individuals.

- Use flipcharts throughout to note down the group’s responses and issues that are important.

- Towards the end ask people how they have found the focus group – do this as a round with everyone having a chance to speak.

- Thank people for their time and their opinions and explain what will happen next with information they have given you.

- When people have left, debrief as soon as possible and write down your own thoughts and feelings about the focus group.

Facilitating the discussion

The aim of the focus group is to encourage focused discussion and the more often the facilitator speaks the more disjointed the discussion is likely to become. The interaction between the focus group members is all-important, as this will generate the rich detail and range of information.

The role of the facilitator is to guide the discussion as discreetly as possible.

A facilitator should:

- Use warm-up techniques to ensure everyone says something early on.

- Encourage members to contribute with prompts such as ‘What do others think?’ ‘Why do you think that?’ ‘Does anyone disagree with this comment?’

- Not offer judgment about anyone’s contribution.

- Be assertive and stop some members from talking too much and at the same time ask direct questions to those who have said very little and wait for them to reply.

- Be flexible. If interesting points arise, take time to follow them up.

- Be sensitive to members’ feelings.

- End the group on a positive note.

Role of the observer

Ideally, if you are running a focus group, you will have a second person present to assist the facilitator. This person might also take notes. If you are paying for a facilitator you might select members of your organisation to volunteer to be the observer. However, remember the confidentiality issues and if you are trying to find out what people think about your organisation then it may not be appropriate to have someone from that organisation present at the focus group. The jobs undertaken by a second person could include:

- Being responsible for the recording equipment.

- Assisting the facilitator if a group member becomes upset or angry.

- Helping to welcome people and set them at ease.

- Observing the discussion and making notes about important points, areas of conflict and tension, topics which provoke humour and other reactions.

- Taking down quotes that seem particularly important or central to the discussion.

- Providing additional feedback to taped discussions and, where there is no taping, to provide the main narrative of the discussion.

D. Other methods

There are a number of other ways of finding out what you need to know. You may find that they suit your approach and the focus of your research and that they complement any other research methods you are considering using. While some of these approaches may be beyond the scope of small organisations, think about adopting some of their principles, as they can provide fresh ways of eliciting people’s views. Some might sound complicated but are quite straightforward as long as you maintain your objectivity and sensitivity to issues such as confidentiality.

Participatory methods

Participatory methods can be used to encourage people to think about different aspects of an issue and to work with others to agree a solution. Using this approach can be a good way of encouraging people who wouldn’t normally attend a focus group or fill out a questionnaire. It is helpful when people are not confident about speaking, enabling them to express themselves in other ways. Some participative methods include:

- Asking people to take photographs of areas near where they live where there are problems of litter or graffiti.

- Using models of the area and asking people to say where things should be built, or how a building should be laid out.

- Discussing an issue, putting lists of ideas on to flip chart sheets and getting people to vote with stickers on the best ideas.

- Setting up a question with yes/no/don’t know answers or better/worse/the same and asking people to vote by putting a plastic counter in a tin or a ball in a bucket.

These can be fun to do and can encourage people to have their say when they have not participated in traditional approaches. However, they do need arranging and you need to ensure you have all the equipment and resources you need. The Neighbourhood Initiatives Foundation has pioneered an approach called ‘Planning for Real’ that is particularly relevant for community development and planning.

You can find out more about participative methods in the additional resources .

Observation

Observation is a research technique that comes from a discipline called ethnography. If you want to know more about ethnography there is some additional information on this in the description of insider and outsider research. Without formally asking questions, you can find out a great deal by watching what is happening. For example:

- You could observe who uses a footpath at particular times of day.

- You could observe what people do when they first come in to a community building – who they talk to, whether they look at ease, if they are welcomed.

- You could have a team of observers recording what activities people are doing in a community centre or park at particular times of day.

- You can record the changes in behaviour over time as participants engage with a project.

“People give their own perspectives of what they’ve seen – their direct observations” (Health organisation)

You would need to be aware of observer bias, make sure that observations are recorded systematically and be sensitive to ethical issues. Do people need to know that they are being observed? If you are just counting how many people are playing football in the park then probably not, but some issues are more sensitive and you should seek permission before you start. You also need to consider if the act of observing someone might change their behaviour.

User panels

This involves users of a service meeting with those responsible for planning and running that particular service. They differ from focus groups in that they are set up to meet on a regular basis for an agreed period of time, say one year, in order to make improvements and ensure the service meets user needs. They are a tool for consultation that actively involves people, with an opportunity to voice concerns and questions and provide feedback.

Things to think about:

For user panels to be really successful there are a number of factors to consider:

- They need to involve a cross-section of users, management and day-to-day service deliverers. 10-12 people is ideal.

- the more commitment shown by senior management, the more influence the group will have – but they must commit to being receptive to any criticism or negative comments.

- Be clear about who you would want on the panel and why.

- Appoint members for a fixed period of time.

- Provide support and funding to enable people to attend, possibly using interpreters for community languages.

- Hold meetings at times and in places that encourage people to attend, not just the ‘usual suspects’.

- Use other means of consulting to avoid total dependence on the panel. It is not an independent organisation.

- Make the time for members to take issues back to other groups in order to gain wider feedback and opinions.

- Take it seriously.

Open and public meetings

These may be one-off events or a series of meetings about particular issues affecting the community. They are open to everyone and are held in public places that encourage people to attend. They are usually advertised through the local press and local networks. Sometimes particular groups are invited to attend and give presentations about relevant issues. Public meetings often have low attendance and those who do go can sometimes be seen as ‘gatekeepers’ of that community; you may need to check out whether their views are indeed representative.

Things to think about:

- People are more likely to attend if the issue affects them directly; publicity should be clear about the impact of the issue on people’s lives.

- Use other methods in association with public meetings; the people who turn up will not be representative of the whole community.

- Provide a meal, refreshments or entertainment to encourage people to attend.

- Use the event to collect more information; try asking people to complete a short questionnaire whilst they are there.

- Use a variety of publicity channels such as newspapers, local group networks, attending local meetings to tell people about it, social media, such as setting up a Facebook page, a lively leaflet.

- Ask people to let you know if they are attending especially if you are planning food and drinks.

- Give some thought to how the meeting will run; who will speak and for how long; what opportunity there will be for people to say what they want, how much of the meeting is about giving information and how much will be focused on information gathering.

- Record what has been said; arrange for note takers to be in attendance or record the meeting. Make sure that people know that this is happening and have given their permission. If you want to take photographs ask for people’s permission first and say what you will be doing with the results.

- Be clear how views from the meeting will be reported and taken forward.

- Provide interpreters, crèche facilities and a loop system to make attendance and participation easier.

Written consultation exercises

This is a formal way of inviting people to make comments on proposals and policies. Written documents are sent to people who are seen as having an interest in the issue or a useful contribution to make. The documents should be clearly laid out and written in simple language with minimal jargon or technical terms. They should not be too long or too technical. Try out the document on someone who knows nothing about the issue and see if it is clear to them. Remember that written papers will exclude those who do not read or write English and that other formats may be required to enable some disabled people to participate.

They should contain the following items:

- Short summary.

- Description of issue, problem or proposal.

- Purpose of the consultation.

- Clear questions for response.

- Explanation of any decision already taken and why.

- Description of what information has already been gathered about the issue.

- Explanation about who is likely to be affected by the proposed changes and in what way.

- Timescale for responding.

- How to send back responses.

- List of those who are being consulted.

- Request for respondents to explain who they are and whose interests they represent.

- Statement that responses will be publicly available unless they request confidentiality.

Things to think about:

- Publicise the consultation exercise.

- Use the internet and social media if appropriate.

- Be prepared to consider printing documentation in other formats and languages.

- Allow enough time for people to consult other groups.

- Give feedback to respondents about the outcomes and decision taken as quickly as possible.

Oral history and story telling

This can be an excellent way of getting a great amount of rich detail and information about particular topics. Often oral history is used with older people as a way of finding out how neighbourhoods have changed. It can also be useful if you want to know how people with chronic conditions cope on a day-to-day basis and what their concerns might be. Asking people to tell their story is a very powerful way of gaining insight into people’s lives and histories. If this is also done in a group context it can provide a supportive atmosphere for people to remember significant events in their own lives and in the life of the community.

Things to think about:

- Find someone who is skilled at working with people in this way; people may recount traumatic events or memories that cause grief and it is important to support people in this process.

- When doing this work with groups it is crucial to invite people with common histories. Otherwise individuals can feel left out and isolated if they are not able to take part in the discussion.

- It can be a good idea to use prompts, such as old photographs, music or objects that might trigger memories and discussions.

These methods of eliciting and representing issues and concerns can be used with many different types of groups about very different concerns, problems and issues. They have been developed with the specific purpose of giving a voice to those who often go unheard. They all hold in common an approach that tries to get beyond words and encourages people to show the issues and concerns in ways that create an impact.

Creative approaches

These can also be very participative and involve people in making or doing something for public view. They can bring people together around local issues in ways that meetings may not.

Videos

Making a community video will involve learning new skills and will promote discussion around what to edit out and what to include. In the process of making the video explanations will have to be given to local people thereby increasing the number of people who know about the research. The end product is tangible and can be used for a variety of purposes from fundraising to promotion. Big Local West End made a film recording changing perceptions of their community in Morecambe, Lancashire.

Photographs

Taking photographs about people or an area is a fairly similar process to making a video. You could hold a public exhibition of photos that show the issues, concerns and strengths of a community. It is a tangible end product and can be very useful to raise further discussions.

“My blocked thoughts and feelings became images.” “Being, living, in a room of everyone’s photographs became a place to see and feel with others locked away thoughts and feelings. To be vulnerable, brave, and honest.”

Murals and paintings

A more permanent artefact is a wall painting or mural that depicts the issues which are important to people. It is preferable to work with a community artist as the end product should be of high quality to gain credibility and show people the value of what they can do. It may be useful to keep a photo diary of the work in progress and notes of the comments made in group discussions in order to produce a publication at the end of the project. here are some examples of community art projects worldwide

Community theatre

This is a very participative way of working with groups of people, with a view to putting on a public performance around specific issues and concerns. It is crucial to work with experienced directors who specialise in this type of theatre, as the high standard of performance will affect the longer outcome. It is a very useful way of working with groups to bring out the issues before performance takes place. It is also useful when the performance is linked to workshops to discuss issues raised. This approach can be used with small groups of performers or with larger groups of up to 50 people. Here is an explanation of the purpose of community theatre and some plays that have been written to explore certain issues